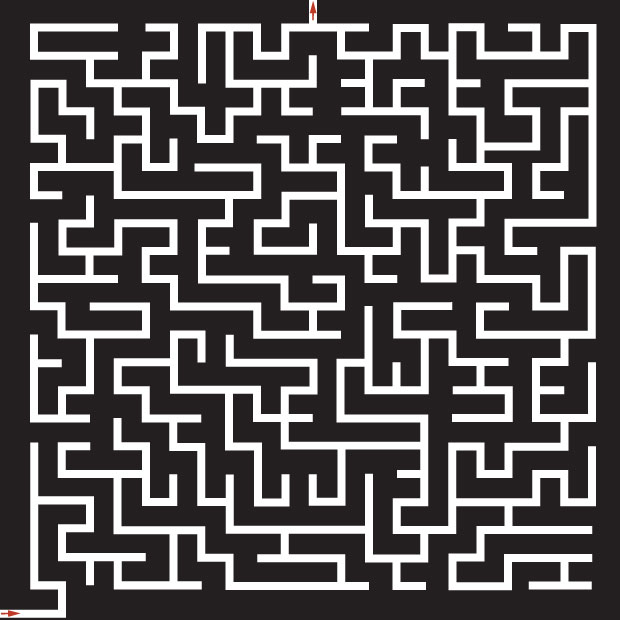

Simplifying the Tangled Maze

STUDENTS LEARN “DESIGN THINKING” FOR LAWYERS

Staff Writer

Law school is supposed to teach students how to think. But like the law itself, ways of thinking evolve, and the problem-solving skills that worked in the past do not always apply to modern practices.

A familiar example: the myriad legal disclaimers that pop up in front of people as they shop or do business online. The language itself may be exacting, but is the message getting across to the consumer, or is it being lost in a welter of perplexing terminology and clumsy, off-putting interfaces?

In that vein, the Law School offered a seminar on the growing field of “design thinking,” or human-centered design, through its Legal Technology and Innovation Concentration. In simple terms, design thinking focuses in on clients’ needs and on working collaboratively to develop solutions that can be tested relatively rapidly. In devising prototype solutions, design thinking deploys sketch pads, sticky notes, scissors, iPads and 3D printers to break down problems and solve them with human needs at the forefront.

Too vogue an idea for the staid field of law? Not in the opinion of the successful attorneys who embrace it, or of the students who took part in “Design Thinking for Lawyers and Business Professionals” during an intersession course last January.

“Lawyers are consistently trained to reduce their analysis to a fact pattern so that they can apply a developed legal approach,” says Alexander C. Gavis, senior vice president and deputy general counsel at Fidelity Investments, one of the two instructors who taught the weeklong seminar. “But only when we really understand what the client’s underlying issues and problems are can we hope to develop viable and lasting solutions.”

“If lawyers don’t understand consumer research and this concept of empathy,” adds Gavis’s teaching colleague, Philippe M. Mauldin, managing director of Fidelity’s Center for Applied Technology, “they may be creating agreements that are completely misunderstood or that go over the heads of customers, ultimately driving up complaints, litigation and business costs. That doesn’t serve anyone.”

The seminar took a hands-on approach. Students were split into groups and took part in real-life exercises, like observing how customers purchase MBTA CharlieCard subway passes in Boston with the goal of designing a better ticketing process. The groups then focused on applying design thinking to more detailed case studies like simplifying the steps people take to file deeds and other legal documents at courthouses or apply for and consolidate student loans. They also worked on a system to help parents give their children supervised approval for online purchases.

The goal, the instructors say, was “to observe and recognize the pain points” that people encounter—those moments when the language or the instructions or the process itself simply grows too legalistic and frustrating—and “try to re-engineer it.” Pointedly, that included talking to consumers.

In the case of the CharlieCards, says Adrian Velazquez JD ’16, doing so meant standing by the card machines, watching how well they worked and interviewing people about the buying process.

“We stepped out of our Law School roles and asked the people who worked and use the ‘T’ what would be a more intuitive and better experience,” he says. “Then we collaborated intensively on how to do that.”

The same process applied when the team took on rethinking “a long and complex government manual” aimed at showing students how to avoid predatory loan practices. “We came up with an idea for an app that would walk people through the best practices in a simple way,” Velazquez says. They did not create an actual piece of software, but used sticky notes and simple visuals to imagine what the app would do.

“I never thought I could develop an app by just doing a prototype on paper,” he says. “Now I think I could make it. I’d have to learn some technical skills, but we were able to build a concept that would work.”

From his perspective as an in-house counsel at Fidelity, Gavis says such skills would make any young attorney more desirable in a tight market. “The lawyers of the next five to 10 years will absolutely need these skills,” he says, “and today’s lawyers and their firms will be taking note, given the pressures on them to be more efficient and consumer-minded.”

“Say a law firm is losing business because the attorneys there don’t appear to be relating well to a new generation of clients,” he adds. “Perhaps the firm needs to rethink its client marketing, outreach and intake processes. If the attorneys develop a fresh understanding and empathy for prospective clients’ problems, this may assist them in relating to and recruiting new clients.”

For Velazquez, the experience of doing hands-on consumer research, working to understand problems, and brainstorming and prototyping—and then presenting simpler ways to cope with opaque legal problems— has him convinced that “every law student should take this course.”