Split Decision

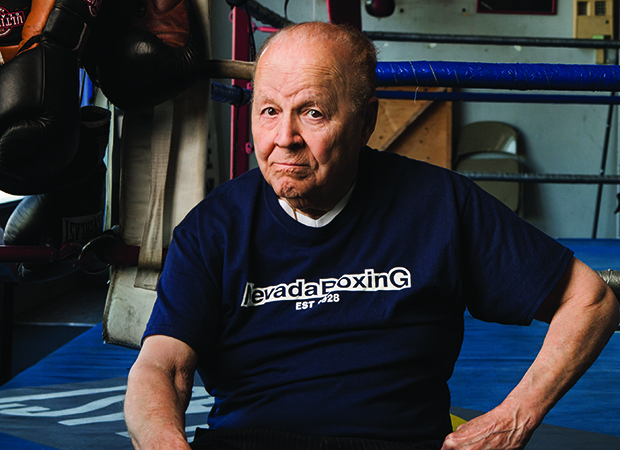

Prizefighting judge AND immigration attorney Herb Santos BA ’58, JD ’60 divides his time between boxers and briefs.

By Kimberly Pryor

Step inside the office of Herb Santos in Reno, Nevada, and it's obvious he's no ordinary attorney.

One entire wall is covered with photos of Santos and celebrities: Bo Derek, Chevy Chase, Burt Reynolds, Bob Hope, and hey, is that Michael Douglas wearing…a garbage bag? The photos are from the 1980s when Santos was on the Nevada State Athletic Commission (NSAC) and attended parties hosted by flamboyant boxing promoter Don King.

“It was raining cats and dogs,” Santos explains of the Douglas photo, taken at a Las Vegas fight. “So they were selling garbage bags.”

At 81, Santos BA ’58, JD ’60 serves as a professional boxing judge while maintaining a full-time law practice.

“He doesn’t slow down,” his 38-year-old son, Cory, says.

Tonight, Santos is judging a team competition, the Italians versus the Americans. Seated ringside, dressed in a pinstripe suit and red tie, he looks robust, even next to the limber young boxers. The bell rings for the final round of the first fight. As the boxers dance around, Santos never takes hi gaze off them. A drunken man yells, “Knock the tattoos right off him!” The Italian partisans scream for their guy. Santos tunes it all out.

When the bout is over, Santos hands his scorecard to the referee with the gravity of a Supreme Court justice voting in a landmark case. Like the other two judges, Santos calls this fight for the American.

Santos, known for his gentle demeanor, seems like the last person who would love boxing. He prays every morning, attends Mass every Sunday, devotes time to pro bono law work, and doesn’t drink or smoke. Vic Drakulich, a boxing referee from Reno, has never heard Santos utter a swear word. “In this occupation that’s pretty rare,” Drakulich says. “He has total class.”

Sister Judith Fogassy is a Hungarian refugee whom Santos helped become a United States citizen. Santos frequently gives pro bono legal advice to Fogassy and her fellow nuns of the Society Devoted to the Sacred Heart.

“Because he gives that extra touch of human kindness, it staggered me that he’s involved with boxing,” Fogassy says. “Because it sounds like such a violent sport.”

Santos, however, appreciates the skill involved in a sport many call the “sweet science.” When he watches a boxer who has mastered this science—like Sugar Ray Robinson or Muhammad Ali—it’s “like watching a great artist perform.”

“Boxers don’t go into the ring just to mindlessly punch each other,” Santos continues. “They’re always thinking in the ring. It certainly is a form of art, just like watching a ballet or good opera. It’s not easy to make someone miss a punch and then within a split second move your body in the position to counterpunch your opponent.”

Santos also believes in the sport’s ability to provide the average person, whom Santos calls “the little guy,” with a real chance to make it big—a story not unlike his own.

The Big Injustice

Santos’ quest to fight for the “little guy” began at 11 years old, when he lived on his parents’ small Connecticut farm with his two brothers and four sisters. One night, his father was returning home from a fishing trip when the vehicle he was a passenger in rounded a blind curve and crashed into a jackknifed semi. Santos’ father flew through the windshield. He survived but required surgical staples in his face. “At that time you didn’t sue much,” Santos says. “I saw the big injustice of him not being compensated for the truck almost killing him. I figured if somebody hurt somebody, they should have to pay for it.” His father, an immigrant from the Azores Islands, was a factory worker and farmer. The accident cost him wages while he recovered.

When Santos was in high school, his friend’s father bought the first television in town. Santos visited his friend’s house to watch Classic Fights, which rebroadcast the legendary matches of fighters like Rocky Marciano and Joe Louis.

“I remember the excitement that you could see in the spectators’ faces,” Santos says. “I didn’t have any money to go to the fights, but I always said, I wish I could be part of that and watch the fights from the spectators’ viewpoint. I was impressed with the lightweights, the featherweights, and the middleweights. They were fast! When [featherweight] Willie Pep threw a punch, sometimes you couldn’t even see it.”

After high school, Santos enlisted in the Navy to see the world. Honorably discharged four years later, he remembered his father’s car accident and decided a law degree would help him seek justice for the average person. A Boston attorney and family friend suggested his alma mater, Suffolk University.

Santos almost didn’t survive his sophomore year at Suffolk. In March 1956, Santos and his roommate, awakened by the sound of their landlord’s barking dog, found the third floor of their five-story building in flames. In pajamas and slippers, they climbed out a kitchen window, onto the garage roof, and scrambled to the ground. Three other residents died. The next day, Santos returned and found his only remaining possession, a $20 bill. Soaked by the firefighters’ hoses, it was encased in ice. “I had to borrow my friend’s notes because my books burned,” Santos recalls.

As an undergraduate, Santos, a government major, was a varsity letterman on the basketball team and a student government representative. He also helped found the University’s veterans club to connect with Suffolk’s other 600 vets.

Santos applied the same concentration to his studies as he now does to judging boxing. “Every Friday, me and one or two other guys would go to the Tick Tock Lounge and party, but not Herb,” says Joe Sasso JD ’60. “Herb studied hard.”

After Santos passed the bar, Boston law firms offered him $50 per week or less. His torts professor suggested Santos become a Judge Advocate General in the military. He followed the advice, and after completing officer’s school at Lackland Air Force Base in Texas, he moved to Stead Air Force Base near Reno. His professor’s suggestion indirectly brought Santos to the state considered the world’s boxing capital.

Before leaving for Texas, he went on a blind date with a Catholic nurse named Jeannette Galipo, who worked at a children’s hospital in Connecticut.

“Jeannette loved children and she was always talking about the children at the hospital,” Santos says. “I figured she must have a good heart.”

Santos and Galipo had three dates before he left for Texas and Nevada, but they wrote to each other every day for nearly two years. Finally, Santos sent her a letter with an engagement ring and the words, “Will you marry me?” They wed in 1962, and Jeannette joined Santos in Nevada.

After four years, he left the Air Force and worked as a deputy city attorney and then district attorney before opening a private practice, specializing in criminal, immigration, and family law.

Immigration law wasn’t initially on Santos’ radar. But when undocumented workers visited his office seeking legal advice, their stories of long hours, low wages, and dangerous conditions disturbed him.

“The business owners threatened them— if they didn’t comply with what the business owners wanted, they would report the undocumented workers to the immigration office,” Santos recalls. “I thought this was immoral, a huge injustice, because it violated their dignity as human beings.” Santos consulted immigration attorneys and began reading books on immigration law and statutes. Soon, helping immigrants became an important part of his practice.

One of his most memorable immigration law cases involved two Chinese refugees who belonged to the spiritual movement Falun Gong, which was outlawed in China. Fearing jail or death, Santos’ clients couldn’t return home. With Santos representing them, his clients were able to satisfy immigration services’ requirements.

“I hate to see anyone persecuted, and that’s what they were doing in China,” Santos says. “When they arrest somebody, they don’t just put handcuffs on them, they pull them by the hair and drag them through the streets. People should have dignity.”

The Little Guy From A Small Town

In the 1970s, Santos visited a travel agency owned by Al Montechelle, northern Nevada’s chief boxing inspector. Santos mentioned his love of the sport, and Montechelle invited him to attend a live match.

“After the fight, Al said, ‘I feel you’re an honest person, and boxing needs honest people,’” Santos recalls. Montechelle asked Santos to keep time and count knockdowns for amateur boxing. Soon, Montechelle felt Santos was ready to judge the amateurs, which he did for two years. Santos in his Reno, Nevada, office; memorabilia from some of the fights he’s judged, right. Santos started “shadow judging,” sitting ringside with three licensed judges and practicing scoring fights. He applied to the NSAC for a professional judge’s license and was approved in 1978. Even today, Santos must attend annual boxing seminars where his judging skills are tested.

At the Larry Holmes vs. Earnie Shavers match at Caesars Palace in Las Vegas in 1979, Montechelle offered some advice about concentration: ignore the trainers yelling, the corner men screaming, the audience roaring. Since then, Santos has judged more than 50 title fights, including 18 world title matches and three world heavyweight championships. In 2012, the World Boxing Council (WBC) named Santos one of the top ring officials of the last 50 years.

Many boxing officials consider Santos one of the sport’s most accurate judges, but criticism is inevitable. In 1982, he was chosen to judge the Larry Holmes-Gerry Cooney fight at Caesars Palace. The day before the fight, after a member of the Holmes camp claimed Santos was too inexperienced, Santos was replaced.

“You feel dejected,” Santos says. “But this happens. Sometimes a promoter or the sanctioning body [doesn’t] want certain judges to judge the fight. It’s just part of the game. You feel bad but you get over it.”

Three years later, the NSAC and WBC chose him as one of three judges for the Marvelous Marvin Hagler vs. Thomas “The Hitman” Hearns fight. A star-studded audience, including George Burns, Kirk Douglas, and Eddie Murphy, eagerly anticipated the long-awaited match. “Herb was selected because we graded judges on an ongoing basis and Herb consistently graded well,” says Sig Rogich, an NSAC commissioner at the time. “He was viewed as a world-class judge.”

Right before the match, Santos recalls, “I prayed to be allowed excellent concentration and that I do a good job. And I prayed that no one gets seriously hurt.”

“Hagler came on like a tiger,” Santos recalls. “Right after he came out he met Hearns in the middle of the ring and started pounding. Hearns got some good shots in, but Hagler just kept on coming after him, almost chasing him around the ring. The first round was really close, but Hagler inflicted the heavier damage. That’s why I gave him the first round.”

Many boxing aficionados consider that fight’s first round the best three minutes in middleweight boxing history. By the end of the second round, Hearns wobbled on his feet. Santos and a judge from England scored the second round for Hagler, while a California judge went for Hearns. In the third round, Hagler knocked out Hearns.

“The scene was like the Super Bowl with all the eyes of the world on this little arena that held about 15,000 people,” Santos recalls. “And here I am, the little guy from a small town, Reno, Nevada, when they could pick judges from all over the world. I realized this would be the biggest fight I would ever judge.”

Later that year, Nevada Governor Richard Bryan appointed Santos to the Nevada State Athletic Commission. “I wanted to get a more sophisticated board with business and legal savvy,” Bryan says, “and Herb brought that to the commission.”

While Santos was on the NSAC, the World Boxing Association (WBA) held boxing matches in South Africa during apartheid while other sanctioning bodies had withdrawn fights in protest. Under pressure, the WBA voted in October 1986 to continue sanctioning South African fighters but to suspend—rather than expel— South Africa from the organization until the country abandoned apartheid. The NSAC commissioners felt this punishment was too light.

“To me, the WBA was condoning apartheid,” says Santos. Three of the commissioners voted to discontinue NSAC’s WBA membership but still allow WBA to hold fights in Nevada. Santos and Sig Rogich voted against the measure.

“Sig and I thought if you ban the WBA membership, how can you justify to yourself to allow them to have fights here?” Santos says.

Santos completed his term with the NSAC in 1988 and resumed judging boxing. Today, he judges fights in the U.S. and internationally. In Mexico, he is a celebrity. Mayors invite him to dinners, and boxing fans take photos with him. Boxing aficionados there remember Santos judged the Hagler-Hearns fight.

Santos’ sons—all attorneys—inherited their father’s passion for boxing. Joel, 47, judges and referees amateur events. Herb Jr., 50, was an inspector for the NSAC in the 1980s. Cory is a former two-time Nevada state boxing champion. After Cory stopped competing in 2009, he and Santos were the first father-son team to judge a world championship fight when the pair scored the 2011 WBC World Female Championship between Mariana Juarez and Asami Shikasho in Mexico.

“Since I couldn’t share boxing with my father, I was able to share it with my son,” says Santos, whose father died in 1965. “To me, that was a dream come true.”

Santos’ close relationship with his sons helped him endure the loss of his wife to colon cancer in 2007.

“She helped more people than I could ever think of helping,” says Santos. “I still talk to her every day.”

Immediately after their mother’s death, Santos’ sons worried they would soon lose their dad. However, says Cory, “Dad wasn’t the one who was complaining and sad and moping. He was sitting there worried about the three of us boys. Here’s this man grieving deeply the loss of his other [half ] and his concern was with his family.”

Santos still has plenty of fight in him. He’ll continue judging as long as his vision is sharp. He wants to break the record for the oldest boxing judge to score a world title fight, which he believes is around 92 years old. “Life is like a boxing match,” he says. “If you keep punching and fighting, you’ll get through it.”