Select Committee

Four staffers at the Edward M. Kennedy Institute—all Suffolk grads—transport Massachusetts high school students to the Capitol as senators

By Erick Trickey

Inside a 1:1 scale replica of the U.S. Senate chamber, 77 high school students rise from their mahogany desks. Dressed in a mix of polo shirts and T-shirts, blouses and skirts, with a few sport coats and ties, they raise their right hands and swear to support and defend the U.S. Constitution. When they’re done, Lou Rocco BS ’12, their presiding officer, bangs his gavel five times.

“Congratulations, senators, and welcome to the United States Senate!” he says. “I am your humble vice president of the United States.”

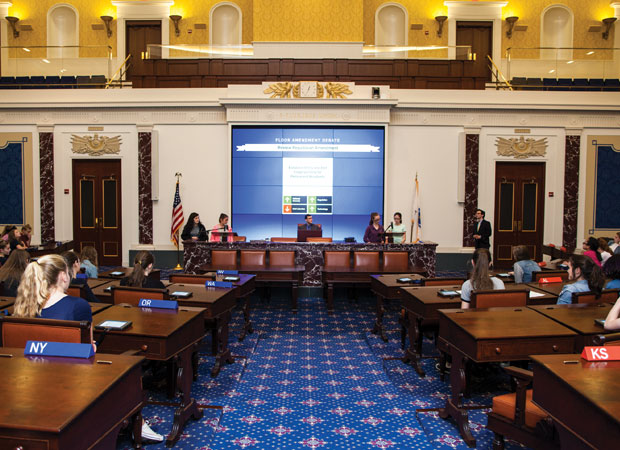

It’s a Thursday morning at the Edward M. Kennedy Institute for the U.S. Senate on Boston’s Columbia Point. Rocco, 26, is at the rostrum of the replica Senate chamber, which recreates the real one in the U.S. Capitol, from the gallery of viewers’ seats high above to the the wall cloths with the look of blue velvet, right down to the purple, floral-patterned senatorial carpet. Rocco is about to lead the daily three-hour simulation in the Senate Immersion Module, where student groups from eighth through 12th grades work together to draft a bill that’s similar to actual Senate legislation.

Officially, Rocco is the EMK Institute’s education program facilitator—which means his job in the Senate Immersion Module on a given day may be vice president, cabinet nominee, or committee chair. Today, like most days, Rocco is performing the veep’s duties as Senate president. He’s the lead actor in a complex performance, guiding students as they explore the convoluted ways a bill becomes a law. Charismatic, with piercing blue eyes and a sharp, narrow face, he strikes up a chummy, Joe Biden–style rapport with the students.

“Some of you might be learning you served in the Armed Forces,” Rocco says as the students read tablet computers to learn about their randomly assigned roles as legislators. “If so, thank you very much for serving.”

Rocco asks who’s playing the Democratic senator from Vermont. A young woman speaks up. Rocco recounts her bio, which really belongs to U.S. Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.)—including his cameos in three Batman films. “This senator went face to face with the Joker and lived to tell the tale!” Rocco says. “Can we get a round of applause?”

Soon, the young senators will try to pass comprehensive immigration reform, an accomplishment that has eluded the actual U.S. Congress. And Rocco, one of four Suffolk graduates employed at the EMK Institute, will guide them through how the upper house of our national legislature works—or is supposed to. “I’m sure this Senate is ready to hunker down and not leave the Senate until you’re done,” Rocco says, betraying a hint of humor about the difference between the simulation and Washington political gridlock.

Different Sides of the Truth

An hour later, in a meeting room a short walk from the Senate chamber, Beatriz Blasco Aguasca MS ’16 plays the role of a Republican caucus leader. Tall, wearing professorial glasses, she has a teacher’s gravitas as she guides the students through a debate about immigration.

The students warm up to their roles as Republicans. Which of them are truly conservative and which are play-acting is hard to tell. One young man says he’s against a path to citizenship for illegal immigrants who arrived in the U.S. before age 16, because of their “parents who broke the law.”

“But do you think that children—it’s not their fault, they didn’t choose?” Aguasca asks. “It’s just my question, trying to challenge your position.”

Aguasca came to Boston from Spain for a master’s in ethics and public policy from Suffolk’s philosophy department. As the students ad-lib their roles as anti-immigration Republicans, her accent creates a sort of meta-awkwardness.

“I don’t like [when] you’re at a McDonald’s, and the workers are making fun of you in Spanish, and you can’t really hear them,” a student says, getting deeper into character. Another senator giggles.

“Yeah, I know, I don’t have that problem,” Aguasca says.

Rather than pretend she isn’t an immigrant on a student visa, Aguasca blends her real identity with her role as committee chair. Some of the senators, pondering a list of proposed amendments to the immigration bill, say they could support the second idea on the list: more funds to process backlogged immigration applications.

“If number two makes the federal government any faster, I’m for it,” says one senator.

“I hope so,” Aguasca says. “I hope so.” She’s experienced the government’s slow processing of visa paperwork herself.

Aguasca’s Suffolk thesis compares how the U.S., Spain, and France have handled the tension between civil liberties and national security. For her U.S. test case, she studied the Patriot Act—knowledge she puts to use at her part-time job as an “ambassador” (a paid internship for students) with the EMK Institute. One of the four Senate simulations the institute runs is a mock reauthorization of the Patriot Act.

Nir Eisikovits, director of the philosophy department’s ethics & public policy graduate program, says Aguasca brought a mature, international perspective to class. Spain’s 1980s transition from dictatorship to democracy informs her scholarship, he says: “The tension between stability and civil liberties has recent resonance. Somebody with those firm democratic, liberal commitments, even though coming from a place where democracy is more fragile, was inspiring to her colleagues. She doesn’t take them for granted, like many in the United States do.”

Aguasca says she often applies her studies in Eisikovits’ political philosophy class in her talks with students at the EMK Institute. John Stuart Mill’s arguments in On Liberty are especially helpful when she’s talking to liberal Boston-area students who blanch at playing the role of a Republican. “[Mill] talks about the different sides of the truth,” she says, “and how, to better understand your beliefs and your position, you need to learn what the other side thinks, but not from someone who thinks like you.”

A place you can learn policy making

Today’s simulation is a reminder of Lou Rocco’s past. One of the three student groups making up today’s Senate is a comparative government and politics class from Medford High School. Rocco graduated from Medford High in 2008. His government teacher, Liz Daneu JD ’06, accompanied her students to the Institute for today’s simulation.

“Lou was not just an exemplary student,” recalls Daneu. “All the dynamism and charisma you saw in that chamber, it was there in high school.”

As Rocco sorted through college acceptances, Daneu counseled him to choose Suffolk. “I said, ‘If you’re on the fence and want to stay close to home, that’s a place you can learn policy making,’” she recalls, noting the University’s long relationship with state government. At Suffolk, Rocco studied American politics and history and interned on Beacon Hill with Senator Patricia Jehlen (D-Somerville).

“He has a very talented approach to taking complex material and breaking it down so it’s interesting for that age group,” Daneu says after watching Rocco lead the simulation. “I told him, ‘You had those kids captivated and engaged. They didn’t once grab their cell phones.’”

Matt Wilding BA ’06, Rocco’s boss, hired him on the recommendation of two history professors, Department Chair Robert Allison and Robert Hannigan. “Lou’s ability to do research quickly and in an organized way, I can tell you with confidence, [reflects the influence] of the Suffolk History Department,” Wilding says. “[It] has a style, a view of how research should be done.”

Recently, Wilding hired another Suffolk grad, Lina Rodriguez BA ’13, as the EMK Institute’s intern and volunteer coordinator. “Suffolk students have yet to let me down,” Wilding says.

A round of applause

Back in the Senate chamber, the student playing the Republican from Idaho delivers a stirring speech in favor of an amendment that would permanently deny citizenship to anyone who enters the United States illegally. The senators vote, and as the totals appear on a screen, they laugh and cheer: It’s a tie.

“Thanks a lot,” Rocco says, to laughter. The Constitution requires him, as vice president, to cast the deciding vote.

With poise, Rocco recites the diplomatic stance he always employs when this happens. “Regardless [of] my personal and political beliefs about this particular amendment,” he says, he believes any amendment or bill “should have a clear demonstrated majority here in the Senate, which this amendment does not.” With a slight smile, he votes it down. The Democrats clap.

Soon the Senate passes its bill, a centrist compromise that pairs a path to permanent residence for illegal immigrants with funding for more border patrol agents. It was a good day, Rocco says afterward—students from different schools worked through their assigned personalities and ideologies to reach the sort of consensus that often eludes the actual U.S. Congress.

“I thought a bill like this, comprehensive immigration reform, would take weeks, if not months,” Rocco tells the students. “But y’all did it in two and a half hours. Give yourselves a round of applause! I wish the Senate were always this efficient!”

Photography by Blake Fitch