Diplomatic Core

Learning to listen and compromise at home gave Timothy Phillips BS ’83 the skills to help warring factions heal and move nations forward

By Reneé Graham

When he speaks of his work in international conflict resolution, Timothy Phillips jokes that his nascent training in high-stakes negotiation was forged not in an academic setting but in a far more raucous and familiar location—the Irish-American household in Boston’s Brighton neighborhood where he grew up. As the youngest of six children, Phillips’ well-honed sense for conciliation and diplomacy, he believes, is innate, and has been a reliable talisman throughout his globetrotting career.

“Being the youngest in a large family, you tend to be more unconventional, you tend to have a problem with authority, and you try to find your own way,” he says. “But we’re all shaped by our environment. For me, that meant I learned, almost unconsciously, how to navigate, compromise, and maneuver.”

As cofounder of Beyond Conflict, Phillips has had ample opportunities to employ and sharpen those skills. Launched in 1992 as the Project on Justice in Times of Transition (PJTT), the organization helps nations with histories of repression, violence, or dictatorship in their transformation to democracy and reconciliation. Phillips fostered the idea that one nation’s leaders could learn from other countries that had previously emerged from social and political turmoil. Shared human experience, he believes, provides a kind of familiar path through what can often be an acrimonious journey. So far, Beyond Conflict has launched more than 70 initiatives worldwide in numerous nations, including Kosovo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Peru, and Colombia. It helped establish South Africa’s lauded Truth and Reconciliation Commission that likely prevented the country, in its fledgling post-apartheid era, from descending into retaliatory violence. The organization also played a pivotal role in the Northern Ireland peace process, paving the way for the 1998 Good Friday Agreement, which ended decades of sectarian violence.

Such figures as former President Bill Clinton and former President Václav Havel of Czechoslovakia (and later the Czech Republic) have praised Beyond Conflict’s mission. In fact, it was Havel, his nation’s first president after the fall of communism, who encouraged Phillips to continue, as an organization, what had been initially conceived as a one-off project.

“Each country will have its own unique experience, but at the end of the day, people would respond to the legacy of repression or trauma as humans, not through their national identity. I knew that intuitively,” Phillips says. “By temperament, I’m a person who asks the question, ‘Is something working, and if not, why not, and how do you shift the paradigm and think differently?’”

Both local and global

With his quick smile and convivial air, Phillips, 54, doesn’t seem like a man who, for more than two decades, has brought together and sat alongside world leaders to lay the groundwork for peaceful resolutions. According to Jessica Stern, a former Beyond Conflict board member and co-author of the forthcoming book ISIS: The State of Terror, “Tim is an interesting person. He’s very easygoing and informal, and he’s very friendly. But he really gets a lot done.” Stern, who is also a lecturer on terrorism at Harvard University, adds, “His manner is deceiving. You would expect someone who does such amazing things to be much more intimidating or formal.”

A lack of affectation is one of the things that drew Phillips to Suffolk, which his older brother Daniel Phillips BSBA ’73, who owns a healthcare executive search agency based in Norwell, Massachusetts, also attended. “I know one of the things I liked about Suffolk when I was there was that Suffolk didn’t have any pretensions, nor did the students. It was about giving people, sometimes the first generation, a chance to go to college or a university, give them a really good education, and give them the skills to be successful,” Phillips says. His father was a salesman for General Electric and Westinghouse; his mother was a homemaker who, after her children were older, became a public school teacher in Boston. Having grown up in a home where politics was paramount—his parents worked on the 1952 congressional campaign of Thomas “Tip” O’Neill, the legendary Boston pol who won the seat vacated by John F. Kennedy’s U.S. Senate run—Phillips was always fascinated by the topic. “My parents knew I was different in that I had broader interests and was much more interested in the world at large,” says Phillips, who is not married. “I was always intellectually curious and interested in ideas and travel. I think my parents encouraged that. My mother, in particular, was very interested not only in politics but issues.”

With Suffolk’s proximity to the Massachusetts State House and Boston City Hall, Phillips was thrilled to attend the University. “You were surrounded by politics; you were surrounded by government; you were surrounded by really incredible role models, whether it was Mike Dukakis, Tip O’Neill in Washington [for whom Phillips, then at Suffolk, would intern], or Kevin White as [Boston] mayor. At Suffolk, you were surrounded by a world that is both local and global.”

Through Suffolk’s work-study program, Phillips landed an internship at Boston City Hall with Lawrence DiCara JD ’76, then a city councillor who was also Boston chair of Massachusetts Senator Ted Kennedy’s 1980 presidential campaign. Phillips took a semester off to work on the campaign.

“A lot of interns, especially the ones from fancy backgrounds and fancy schools, sometimes think they’re ready to be secretary of state. Tim was much more pragmatic. He had to learn from the ground up,” says DiCara, now a partner at Boston law firm Nixon Peabody. “He was a street-savvy, grassroots political worker. I used to joke that I really don’t need people to write position papers; I need people to put up signs. He understood that, and I’d like to think that a lot of what he learned dropping leaflets in Brighton and elsewhere has helped him be very pragmatic in what he’s doing now.”

A playful thinker

After Suffolk, Phillips spent a year studying international relations at the London School of Economics, then returned to the United States in 1986 and worked on the Democratic primary for the retiring O’Neill’s congressional seat. Following the election, he landed a job with BMC Strategies, a Lexington, Massachusetts-based company that handled public affairs and issues management for environmental and energy companies in New England. As an account executive, Phillips was assigned to work with the Coalition for Reliable Energy, which promoted mixed energy solutions, including nuclear power. “I thought, ‘Well, there’s a lot of opposition to nuclear power, and I’m against it as well.’ But it was my job, and I decided to see what I could learn about it,” Phillips says. “It wasn’t just about promoting nuclear power; it was about a mixed energy picture.” Through the coalition’s board that, Phillips says, included “a couple of Nobel Prize winners, some eminent scientists from MIT,” he began to learn about the greenhouse effect. He would soon organize the discussion - “Understanding Global Warming: A Seminar for Journalists” at Harvard University attended by 125 members of the media.

His interest in global warming led him to co-found Energia Global International in 1991, which developed and operated privately owned renewable energy facilities in Latin America to reduce climate change. “Someone told me a long time ago that if you do interesting things, interesting opportunities will come your way,” Phillips says. That opportunity—which would lead to Beyond Conflict—was an invitation to the prestigious Salzburg Global Seminar in Austria, a two-week gathering of current and future leaders to solve issues of global concern. Among the NGO leaders, parliamentarians, and environmentalists, Phillips befriended several Central and Eastern European dissidents, and he asked them how their countries were dealing with often-brutal legacies of repression, dictatorship, and human rights violations. “They were still euphoric about the collapse of communism, and they were writing constitutions, designing market economies, and building new institutions of governance,” Phillips says. “But these were key issues they were just starting to think about.”

He approached the seminar’s director and suggested a special session for post-communism leaders “to talk about how they deal with the past in order to strengthen the transition to democracy,” Phillips recalls. “And rather than having so-called experts come in from the U.S. and Western Europe, I thought, ‘Why not bring in leaders from other countries that have gone through transitions from dictatorships to democracies?’” Phillips soon realized this subject was worthy of its own conference. He connected with businessman and philanthropist George Soros, who funded the event, and Wendy Luers, founder and president of the Foundation for a Civil Society, who offered funding and support staff. Her husband, William, was the former U.S. ambassador to Czechoslovakia and a friend of Havel, who led his nation’s “Velvet Revolution” from communism to democracy. Six months later, the Project for Justice in Times of Transition’s conference was held in Salzburg.

“We don’t know what it’s like and shouldn’t be telling anyone anything,” said Beyond Conflict co-founder Luers in a 2000 interview about the group’s mission. “We are the conveners, the facilitators, the interlocutors, the spark. We bring those who have lived through such experiences together. And we know how to listen.”

Among the dozens in attendance were Havel; Adolfo Suárez, Spain’s first prime minister after longtime dictator Generalissimo Francisco Franco; a chief prosecutor from the post-World War II Nuremberg Trials; and the leaders of the Truth Commissions in Chile and Argentina. Still, its success wasn’t a given, Phillips says. “I would say that the biggest challenge at times was to get leaders who were in the midst of a protracted conflict to believe that peaceful change was possible and that they could learn from the experience of others,” he says. “Too often, people who have suffered war, division, and mistrust think their situation is unique and that they can’t learn from others. That nobody has suffered the way they suffered.” Phillips recalls the first day of the inaugural session in 1992 when the participants were “talking past each other. Then all of a sudden, the Eastern Europeans heard [former Argentine] President [Raúl] Alfonsín say, ‘We have no tradition of compromise. As a matter of fact, in Spanish, we don’t really have a word for compromise.’ People understood that others had struggled in their transitions as well. All of a sudden, the similarities started coming out and the differences started fading away. At that point, I knew we were onto something important just from the response of the people there.”

Stern calls the work of Beyond Conflict “really courageous” and praises Phillips’ open-minded approach. “He’s not a conservative thinker,” she says. “He’s a playful thinker, who always wants to push boundaries.” Recently, Beyond Conflict has been working with MIT researchers to explore the relationships between violence, the brain, and universal human reactions to conflict. It is yet another tool for Phillips to better understand how nations become destabilized and embroiled in unrest. Whatever the means, he says, dealing with politically fractured nations trying to remake themselves into a new whole, while coming to terms with a troubling history, takes patience. He tells all participants as much. Yet the results he has witnessed for nearly a quarter-century, from South Africa to Sri Lanka, have proven the efficacy of his idea that shared human experience can help guide people and nations from a history of darkness toward a promising future.

“I was brought up in my family and community with the notion of giving something back, and doing something useful and constructive,” Phillips says. “Seeing the ways in which other countries had gone that extra mile to resolve intractable conflicts added to our own commitment to make things work. Our work is to convince people that change is possible, and that they can achieve it.”

Executive Privilege

Timothy Phillips has worked alongside many world leaders. Here, he reflects on a trio of presidents he has gotten to know since he co-founded Beyond Conflict in 1992:

Timothy Phillips with Mikhail Gorbachev

“Mikhail Gorbachev was a very warm, approachable, and funny individual who told some very funny jokes about life in the USSR. I grew up during the Cold War and all the previous Soviet leaders were dour, threatening, and a bit intimidating, and here was this very approachable and regular human being.”

Timothy Phillips with Bill Clinton, former British Prime Minister Tony Blair and his wife Cherie

“While I knew from afar that Bill Clinton was a master politician and brilliant, I found that he truly and deeply cared about people, and in a personal way. Once when traveling with him overseas, an anonymous person pressed a self-published book in the president’s hand and I later saw him reading it. I asked him why he would take the time to read it, and he looked at me in the eye and said, ‘Everyone has a story to tell and they deserve to be acknowledged.’”

Timothy Phillips with Vaclav Havel and Beyond Conflict co-founder Wendy Luers

“Vaclav Havel was a brilliant playwright, a courageous dissident, and the celebrated and much admired leader of Czechoslovakia after the collapse of communism. What I found most interesting was how shy he was as an individual. He spoke softly, never dominated the room, or felt the need to. He was that rare political leader whose mind, writings, and moral stature spoke for itself without any ego.”

Participants at Project Initiative, "Dealing with the Past" in Cape Town, South Africa, 1994

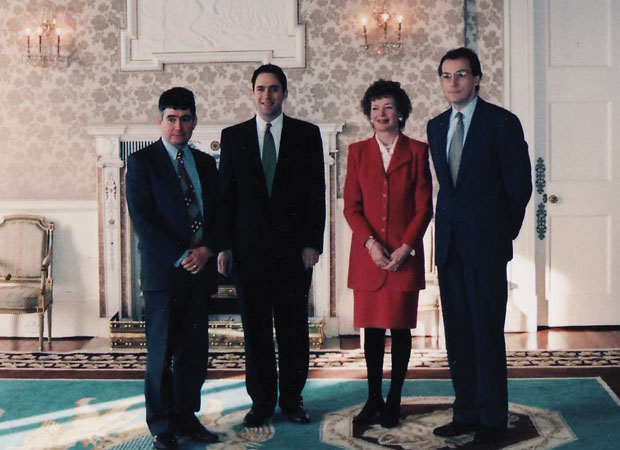

With Paul Arthur, Eric Nonacs, Mary Robinson, then Ireland's president, in Northern Ireland in the 1990s