Race To the Top

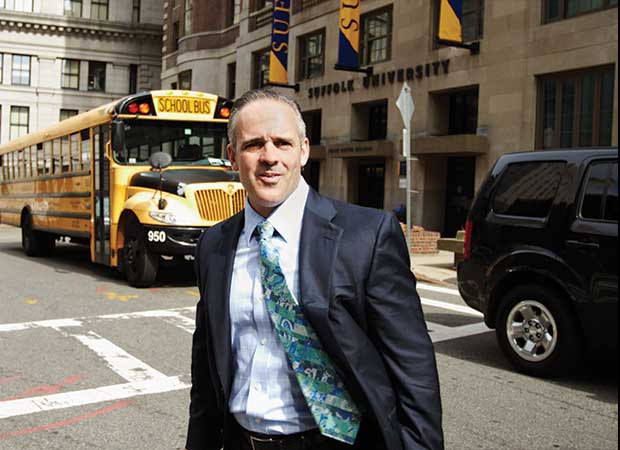

Bay State Education Chief Matt Malone, BA ’93, was given 100 weeks to make his mark in his home state. The clock is ticking.

By Amy Crawford

"If you saw my high school transcript, it would be an embarrassment," says Matthew Malone BS '93. "I wasn't a student in high school. I graduated without learning my times tables. At Suffolk, I was on 'double-secret probation'--my GPA was so low they were going to throw me out."

It’s a startling admission from a man who, in January, became secretary of education for Massachusetts, putting him in charge of the office that sets and carries out education policy for the entire state. Over the past two decades, Malone has risen rapidly through the ranks of public education in the Commonwealth, from stints as a substitute teacher in Boston to positions as district superintendent in Swampscott and Brockton. But he has never been coy about his early life.

Diagnosed with a learning disability before kindergarten, he was an indifferent student who struggled in high school, dropped out of college, and nearly flunked out again when he came to Suffolk for a second try. But Suffolk, Malone says, never gave up on him, and he was able to turn his grades around and graduate, eventually supplementing his BS in history with a PhD in educational administration from Boston College. Today, his improbable journey from a special education classroom to a corner office on Beacon Hill is what inspires Malone to ensure that every young person in the state has a chance to be successful.

“My point is, we don’t give up on kids,” Malone says, explaining why he is frank about his own struggles. “We’ve given up on way too many kids, but if we don’t, maybe they’ll grow up to be secretary of education.”

On the Front Lines

Standing 5 feet 3 inches tall, Malone has the pugnacious bearing of a terrier and the tight haircut of the Marine sergeant he once was. It’s a tough look that belies an enthusiastic, upbeat demeanor, which charms everyone from state senators and their interns to the troopers who patrol his office building at One Ashburton Place. But Malone is at his most effusive when he witnesses an extraordinary act of teaching.

“This teacher exemplified the best of our profession,” he gushed after a recent visit to the Perkins School for the Blind in Watertown, where he watched an instructor use 3D models to help a class of blind children understand the double-helix structure of DNA. “She was an ass-kicker, in the best of ways.”

Massachusetts remains at or near the top of most rankings when it comes to student achievement, but Governor Deval Patrick, who picked Malone for the secretary position based largely on his successful stewardship of Brockton’s public schools, believes the state could do better. Patrick and Malone want Massachusetts to focus more on early education, improve access to college, and work on closing the achievement gap for poor and minority students. These are ambitious goals, and Malone and his staff of 13 have been busy since his appointment in January.

“The secretary really wants us to make sure, in the months we have left, that we are implementing as much as we can in a meaningful way,” says Matt Wilder BA’05, Malone’s communications director and right-hand man. That means visiting as many schools and colleges as possible, ensuring that educators on the front lines have the help they need from the state and that they are working together to meet the administration’s goals.

This schedule can be grueling, hard on Malone as well as on his wife and two young children. Since his appointment, the secretary’s work has taken him to nearly every corner of the state. He and Wilder usually spend three days a week traveling, with Malone piloting his family car—a blue Nissan Murano with nearly 140,000 miles on the odometer—while Wilder, in the passenger’s seat, manages Malone’s overcrowded schedule. The rest of the week is spent in Boston, where, on a typical day, Malone may accompany Governor Patrick on an early-morning visit to a school,return to his office to catch up on e-mail, cross the street to the State House to meet with lawmakers, participate in a conference call with state officials, and then head over to UMass Boston for a Q&A session with graduate students studying urban school leadership.

“Sometimes we go whole days without eating,” Malone says with a laugh, as he rushes to yet another meeting.

“We’ve started traveling with MREs,”Wilder jokes, explaining that Malone was given a package of military “Meal, Ready-to-Eat” during a recent visit to a Junior ROTC camp.

When he’s lucky, Malone has a few minutes to pop into the Capitol Coffee House, an old-fashioned diner that he visited almost daily during his years at Suffolk. Proximity to his old hangout, Malone confides, is one of the perks of his new job on Beacon Hill.

“This was the epicenter—people used to meet here,” he says. “When I was sworn in as secretary, the first thing I did [afterward] was come here.”

“He hasn’t changed at all,” says Sam Maione, who has owned the breakfast and lunch spot since 1977. “Just gotten grayer!”

“These guys, they’ve known me for 25 years, but they still bust my chops like I’m 20 years old,” Malone says, as Malone fills his coffee order. Then it’s out the door for another meeting at the State House.

A Stigma

It’s a daily schedule that might surprise people who grew up with Malone in Newton Upper Falls, a close-knit, middle-class neighborhood in the city of Newton. Gregarious and athletic, the young Malone had a knack for forging friendships that have lasted to this day. But academic success came less easily.

“He always was passionate about certain things,” explains his mother, Judy Malone Neville, who retired this year after a long career as a teacher and school administrator.

“He did well in school in subjects that he really liked, and not so well in subjects that he didn’t want to put the time into.”

Malone’s difficulty with school also had a neurological basis. Before kindergarten, he was diagnosed with dyslexia, a learning disability that, without diminishing a person’s intelligence, affects the brain’s ability to recognize and interpret words, letters, and symbols.

“He was about four,” Malone Neville says, recalling the first time she noticed her son’s tendency to reverse letter order, a common sign of dyslexia. “He came home from a birthday party, and they had made paper crowns. I noticed his said ‘TTAM’ instead of ‘MATT.’”

Today, schools make an effort to keep children with learning disabilities in mainstream classrooms. But when Malone was in school in the 1970s and ’80s, students who needed special help were often pulled out of regular classes and sent to a different room, with little thought to how separate treatment might affect their confidence.

“The teacher says, ‘Everyone take out your reading books—except you, Matt, you’ve got to go downstairs,’” Malone recalls. “You feel inferior. Really, there was a stigma.”

Tired of being singled out, Malone decided not to accept help from special education teachers when he started ninth grade. But while he kept his grades high enough to avoid getting kicked off the wrestling team at Newton North High School, by the end of his senior year he was beginning to feel he’d had enough of school. He joined the Marine Corps

Reserve before graduation, made a halfhearted attempt at college with a partial semester at Rhode Island’s Roger Williams University, then took a job with a party rental company. Then the Marine Corps ordered him to go full-time, sending him to field-radio operator school in California.

“I was out there, and I realized college was actually more fun than that,” Malone says.

For his second try, Malone chose Suffolk, where at first he continued to struggle. But in 1991 his Marine unit was deployed to Saudi Arabia, for Operation Desert Storm. He returned from the war with a new maturity,the discipline to buckle down and focus on his studies, and the sense that his Suffolk education was worth the effort.

“It was like, ‘Hey, I’ve got this great advantage to better myself,’” recalls Tom Fryar BSBA ’93, a good friend at Newton North and at Suffolk, who watched Malone transform from a happy-go-lucky teen to a “driven” college student. “He was all about academics.”

“A lot of us stumble early on,” says Robert Allison, chair of Suffolk’s history department,who recalls Malone as an “engaged and lively” presence in his seminar on the Civil War. “Matt understands that education isn’t just something that happens to you because you’re under the age of 21.”

Allison, who stayed in touch with his former student over the years, received a surprise visit when Malone returned to Beacon Hill in January, after having been sworn in as secretary of education.

“It was one of the proudest moments of my career,” Allison says. “The biggest reward we get as teachers is hearing that we’ve had an influence on a student. And here he is, really in a position to improve education!”

Graduating from Suffolk with a newfound appreciation for learning, Malone decided to try being a teacher. He took a position as a substitute in the Boston Public Schools, where one of his first assignments was to fill in for a teacher who had been badly injured during a fight between her emotionally impaired students.

“I had three sixth-grade boys and me,” Malone says. “Some days they would sit on your lap and you would read to them, and other days they would go, ‘F--- you!’and punch you in the face because of some trauma that happened in their lives.”

At first, Malone was at a loss—he had no training as an educator, and these were some of the toughest students at Martin Luther King Jr. K-8 School in Boston’s Dorchester neighborhood. Hoping to inspire the three troubled boys, all of whom happened to be African-American, Malone drew on his experience at Suffolk, where he had majored in history with a concentration in black studies. Malone guided his students as they researched figures like Marcus Garvey, Ida B. Wells, and Booker T. Washington. The curriculum seemed to resonate with the boys, and by the time Malone’s assignment ended eight weeks later, he was hooked on teaching.

“It was such a challenge, and you realize, these kids need you!” Malone says. “They need someone that’s not going to give up on them.”

It was a lesson that Malone took to heart as he went on to earn his teaching credential, and commit himself to urban education, first as a history teacher, then as principal of Monument High School in South Boston, and later as an administrator in San Diego, California,and superintendent of public schools in Swampscott and Brockton in Massachusetts.

Michael Perryman, a 1999 graduate of Dorchester’s Jeremiah E. Burke High School, remembers “butting heads” with Malone, his U.S. history teacher. One of the school’s top basketball players, Perryman was rendered temporarily ineligible for the team because Malone—unlike other teachers at the troubled school—declined to let the star athlete pass without having done his classwork. All the pleading in the world could not persuade Malone to change Perryman’s failing grade, and the teen wound up sitting on the sidelines as his team won a championship.

“That was probably the hardest moment of my life,” says Perryman, who now trains sales staff for Apple and recently started his own media business. “I was so used to being the big man on campus that being held responsible for myself—it plays a big role in who I am today.”

A Field Commander