Ray of Hope

Cancer patients depend on an invisible beam and the Suffolk graduates who guide it.

By Amy Crawford // Photographs by Adam Detour

Deep beneath Massachusetts General Hospital in downtown Boston sits a 200-ton cyclotron, a powerful accelerator that spins hydrogen ions into a high energized beam of proton radiation. The beam emerges from the cyclotron and speeds through the hospital, bent and focused along the way by a series of magnets as large as SUVs. This afternoon, its destination is a 100-ton rotating gantry. An apparatus used to direct the beam, the gantry soars three stories high and looks like it belongs on the International Space Station. As it grinds and whirs, a cone on the other side of a wall rotates into position, ready to guide the proton beam deep into the brain of a teenage girl.

She lies perfectly still, her head held in place by a mask of stiff white mesh while a shock of her long red hair hangs over the edge of the mechanized table. With a brief series of beeps, the beam passes through the patient’s skull and into the meningioma that is threatening her life.

After a few minutes, her treatment, which she has undergone daily for more than a month, is over for the day. Once released from the mask and helped off the table, the girl hugs her father, puts her earrings back on, and bounces out of the room with a palpable sense of relief, her face still bearing the red crosshatched marks of the mask.

She is one of up to two dozen patients that senior radiation therapist Ryan Connolly BS ’07, CRT ’09 and his colleagues will see today at the hospital’s Francis H. Burr Proton Therapy Center. Once her treatment is complete, the four therapists quickly prepare for their next patient, a freckled teen with a craniopharyngioma. She has asked them to play a CD of upbeat dance songs while she undergoes her treatment.

“A lot of times we get to know patients by their music choices,” jokes Connolly, 28, as he helps the teen onto the table and quizzes her about school. Although his cheerful disposition might seem incongruous with the gravity of his patients’ conditions, putting patients at ease is an important part of his job. “Most people see radiation as a terrible force that only causes damage,” he notes. “But here we use it as something beneficial, to cure cancer. How many people get to say that?”

Connolly didn’t have to go far after graduating from Suffolk’s clinical radiation therapy program in 2009. Like many of his classmates, he barely had time to graduate before he was snapped up by Mass General, which boasts one of the best—and most in-demand—radiation oncology departments in the world. The three-quarters of a mile between its headquarters and Suffolk’s campus is a well-trod path. Although the University’s radiation therapy program began only two decades ago, today its graduates dominate Mass General’s radiation department, and 30 of the hospital’s 76 therapists are Suffolk alumni.

Samah Taha

A TERRIBLE PHONE CALL

It may be one of our best weapons against cancer, but most people give little thought to radiation therapy until they or someone they love faces a life-changing diagnosis. When, as a Suffolk sophomore searching for a major, Connolly noticed a poster on campus advertising the department, “the only thing I knew about radiation was that it was bad,” he says. He flashed back to high school, when he spent a month in Japan as part of a student exchange program. The trip included a visit to Hiroshima, which was destroyed by an American atomic bomb in 1945.

“My first education about radiation was devastating,” Connolly says, recalling the tour of Hiroshima’s Peace Memorial Park. “It was destructive, it was a force not to be reckoned with. I saw this poster for radiation therapy and I was like, ‘What? This is crazy!’”

His interest piqued, Connolly did some research and discovered a calling. He had always liked solving puzzles, and radiation therapy requires figuring out the best way to position patients and equipment in order to deliver the smallest possible dose of radiation. He also knew the daily interaction with patients and fellow therapists, who work closely in small teams, would suit his gregarious personality. Plus, the self-identified geek, whose punk rock earrings and spiky haircut offer a playful contrast with the sober white lab coat and scrubs he wears to work, was drawn to the powerful, massive equipment and rapidly evolving technology.

“These are incredibly complex machines that are being used to help somebody,” Connolly explains. “Seeing radiation controlled in such a manner that you could actually do good with it was mind-blowing to me.”

Radiation therapy, which uses X-rays, gamma rays, or highly energized particles like protons to kill tumor cells by damaging their DNA, has been used to treat cancer for more than a century, but it has become increasingly effective over the past few decades. Now prescribed for more than half of all cancer patients, it may be our most powerful weapon against a disease that still kills more than half a million Americans every year. But radiation can also be very dangerous, since a dose that is too big, or that doesn’t enter the patient’s body in exactly the right place, can damage healthy cells and even cause cancer.

Radiation therapists take on an enormous responsibility, says Kathy Bruce, director of business development for Mass General’s radiation oncology department and an adjunct professor at Suffolk. “When you work in a place like this, you have to be a cut above.”

In the early 1990s, Bruce says, Mass General decided to move toward requiring its radiation therapists to have bachelor’s degrees, rather than coming straight to work after a two-year program. But the hospital needed to ensure a steady supply of qualified therapists, so Bruce approached Suffolk about creating a program. The technology was more advanced and treatment plans were becoming more complex, she explains. Demand was growing for therapists who were, as Bruce puts it, “educated,” not merely “trained.” Suffolk, which graduated its first class in 1998, would help meet that need.

To graduate with a bachelor’s degree or postbaccalaureate certification that will qualify them for hospital jobs, students must complete more than 1,300 clinical hours, during which they shadow therapists and learn the profession on the job. Most do their clinical rotation at Mass General, so when those who are later hired as full-time therapists show up for their first official day at work, they already feel like veterans.

Samah Taha CRT ’13, who now works with photon radiation at Mass General’s Clark Center for Radiation Oncology, spent her student days pulling 8- or 10-hour shifts at the hospital, often followed by two to three hours of class. “They were really long days!” she exclaims. Taha is on a brief break before her team’s next patient, a 60-year-old man with a malignant chest wall tumor, arrives for a dose of preoperative radiation.

For Taha, the drive to learn the material and develop her confidence and skills was deeply rooted. The middle daughter in a close-knit Lebanese-American family in Burlington, Massachusetts, Taha had watched an older cousin succumb to brain cancer and an aunt battle breast cancer. Her father survived a bout with Hodgkin’s lymphoma before she was born. A younger cousin, whom she last saw dancing happily at a family wedding in Lebanon, died last year at age 10, after spending half his life fighting a brain tumor. And one evening in January of 2012, Taha was on campus when she got a terrible phone call from her older sister. Their mother, Gondolina, had been diagnosed with thyroid cancer.

Gondolina had her thyroid removed at Mass General, where Taha was going several days a week for her clinic hours. A firm believer in education, Gondolina insisted her daughter not take time off from her studies. But on a lunch break the day after the operation, Taha went upstairs to visit and was struck by her mother’s condition.

“I just remember she was in a lot of pain,” Taha says, explaining that Gondolina, a preschool teacher, was usually full of energy. “She wasn’t herself. It was very hard, seeing her in a hospital bed.”

Gondolina Taha has since made a full recovery, and she credits her daughter with helping her navigate the medical system and understand her disease.

“She told me everything about the treatment, she explained everything,” Gondolina says. “She’d tell me, ‘Look at this patient, she survived!’”

For her part, Taha says the experience helped her to be more compassionate toward her patients. But it can be difficult to balance that compassion with the need to maintain a clinician’s professional detachment.

“Sometimes she comes home and she’s so sad,” Gondolina says. “I tell her, ‘Look at the job from two sides.’ Think of all the people she’s helped! She’s still trying to keep her emotions separate. I tell her, ‘You’re working on it, but you’re a human being.’”

Radiation therapists must be technically proficient, knowledgeable about anatomy and medicine, focused, disciplined, and diligent—but the most challenging part of the job is often psychological.

Meg Kearney

“You try to separate your personal and work life,” says Meghan Kearney BS ’05, MS ’09, a team lead therapist who currently focuses on pretreatment simulation. “But then you see the really depressing cases or you meet the really young patients, and it’s hard not to let that get to you.”

At times, working in radiation oncology can feel like being in a foxhole, fighting a war against cancer with a close group of fellow soldiers. The four-person teams who manage each machine have their own inside jokes, and gallows humor is not uncommon. “It’s a small community, and not everyone knows what you go through,” Kearney says. “Who knows better than fellow radiation therapists?”

Kearney, a tall 30-year-old with expressive eyes and the light step of a dancer, is known among her colleagues for her way with patients. When an overweight lung cancer patient needs a dozen people to help heave him onto the table, Kearney smoothes over what could have been an embarrassing moment. “Look at the team you’ve got!” she says cheerfully, as the therapists and nurses slide the man from his gurney in one easy motion.

Like many of her colleagues, Kearney relates to patients by drawing on personal experience. As a student at Suffolk, she looked up to Angela Lombardo, the radiation therapy program’s tough but kind director. But a year after Kearney graduated and took a job at Mass General, Lombardo received devastating news: the 38-year-old was diagnosed with sacral chordoma, a rare and often fatal cancer.

“It was shocking,” says Christine Cerrato BS ’98, technical director for radiation oncology at Mass General and one of Suffolk’s first radiation therapy graduates. Cerrato, who has also taught classes at Suffolk, had grown close to Lombardo over the years.

Christine Cerrato, technical director for radiation oncology

In addition to being dismayed by the diagnosis, Lombardo’s friends and colleagues were surprised that her doctors had caught the cancer at such a late stage. “We are in this field and you would think that those things wouldn’t happen,” Cerrato says. “But it still did.”

“It hit really close to home,” Kearney says. “The worst part is, I remember being in my senior year and she would have this back pain. Sometimes in this field, you can tend to be a little bit of a—I don’t want to say hypochondriac, but you think of things a little bit more than anyone else would. I remember her having this back pain and saying, ‘I swear to God, if I have a chordoma. . .’ And literally, she did, which is so terribly ironic.”

Lombardo received radiation therapy at Mass General, where many of her former students were already on staff. But the treatment was not enough, and she died in 2008. Her loss was a blow to Kearney, Cerrato, and others who had known her at Suffolk, but they say her memory inspires them to keep fighting.

“You should treat every patient as if they’re your own family member,” Kearney says. “Sometimes you can lose sight of that, but those experiences that hit close to home put everything into perspective.”

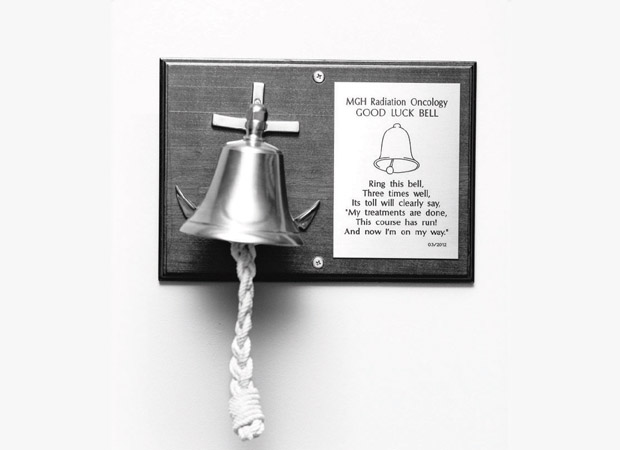

RING THAT BELL

Whatever the root of therapists’ compassion, patients say it helps them get through difficult times.

“I had dreaded it,” says Jim Gaffey, who was treated for prostate cancer in 2009 by a Mass General team that included several Suffolk graduates. “At first it’s like going to the dentist to get a root canal—you’re not there to have a lot of laughs.” But his team’s skill and, yes, good humor put him at ease. “They were professional, organized, efficient. There was never a day in the eight weeks that there was ever a problem.”

The Framingham, Massachusetts, resident, 69, is now in good health, and he has kept in touch with his therapists over the years, regularly driving into Boston to deliver homemade chocolate chip cookies.

“Here are these people who saved my life!” he says. “How can you really thank them enough?”

Radiation therapists know that they can’t save everyone, but focusing on the good they do helps them get through long and sometimes draining days. In the waiting room, patients in gowns pass the anxious time before their appointments leafing through magazines or watching videos on their iPads. They may have traveled long distances to get to the hospital. They may be dealing with pain, fatigue, and nausea. Often unable to work, many are plagued by financial worries—on top of the fear that comes with not knowing whether the treatment will be enough to save their lives. But on a wall near the exit, there is a brass bell, which, according to hospital tradition, every patient rings three times after his or her last treatment. Its bright sound echoes through the department, bringing a hopeful smile to the face of any radiation therapist who hears it.

“The best part of my job,” says Samah Taha, “is when they ring that bell.”

Read more about Jessica Mak, radiation therapy program director at Suffolk, in the 2014 Winter issue of SAM.